Vindicated wherein?

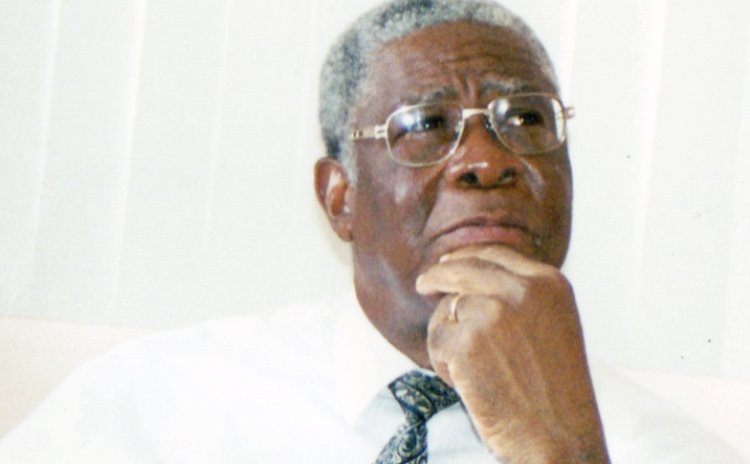

Rev. Dr. William W. Watty

The Chronicle's front page of the October 16 issue was taken up almost entirely with an over-ruling of the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council of a judgment that was handed down by the Eastern Caribbean Supreme Court in favour of Mr. Lennox Linton, against which Mr. Kieron Pinard-Byrne appealed.

I say "almost entirely" because I doubt any reasonable reader would suppose that the Law Lords could, in good conscience, endorse everything that was written as plausible commentary on their judgment. I doubt that they would agree that their judgment could best be evaluated in terms of vindication and condemnation. I refuse to believe that "a media personality turned politician" was given any more consideration in their deliberations than the matter, when it was judged in the Eastern Caribbean Supreme Court, was influenced by the accident of one of the litigants being Irish and white. Nor did I understand that the judgment, as handed down by the Privy Council, intended an apology by Mr. Linton to anyone, including Mr. Kieron-Byrne, or else it would have been explicitly included in the punishment that was imposed.

All these snide pretensions can therefore be interpreted as an attempt to extract maximum advantage out of success, regardless of the limits of the success or the merits of the disadvantaged. That could hardly have been the purpose of the judgment that was handed down. It was nothing less and certainly nothing more than the outcome of a strict interpretation and application of the Law, as it stood, to the particular grievance. Not even the Law Lords, to my knowledge, were endued with psychic powers to discern precisely, and infallibly determine, beyond the particular issue before them, what was the truth, who was wrong and who was right. They could only rely upon such evidence as was presented, and interpret and apply the Law, as best as they could. A just Law, correctly interpreted, will tend to yield a judgment that is fair. An inadequate Law, correctly interpreted will encourage an unsatisfactory result. Similarly an unjust Law, correctly interpreted, will prohibit and even frustrate a judgment that should be just. Therefore judgments reached in the Courts do not and cannot, ipso facto, validate. The vital evidence, not forthcoming, is no guarantee that the vital evidence does not exist. Nevertheless, when the evidence is insufficient for a determination of guilt, innocence must be presumed – not established, only presumed. That is about as far as the Courts can go. There can therefore be no finality anywhere on our planet. All our earthly assizes are, at best, dress rehearsals for another Assize at which all the books will be opened and all the evidence will be presented. Then, and only then, will "validation" have meaning. In the meantime all we can safely rely upon is the voice of conscience, accusing or excusing, and alerting us, in its own way, to the summons "Oyez! Oyez!"

Therefore, overblown, self-serving hurrahs of vindication, based on earthly judgments, beg questions, and the more overblown and self-serving, the more questionable. The very demand for an apology speaks obliquely. It suggests that the final judgment handed down by the Privy Council did not go far enough. Its "vindication" was inadequate vindication. Only the last ounce of flesh could suffice. Mr. Linton must not only be made to pay the uttermost farthing. He must crawl on all fours and contritely beg for pardon. Why? What is the problem? What, really, would such "vindication" prove?

Of course, Senior Counsel Mr. Anthony Astaphan, true to form, had to go off-tangent and dance the extra mile, heaping upon Mr. Linton epithets of scorn and reproach – "dishonest", "malicious", "irresponsible" and "profoundly" so. Under the guise of moralizing upon a legal judgment, he had to scatter his aspersions, even to the dragging in of a former Prime Minister. And for what? A political advantage? A personal pique? As I have noted before, I find that mentality most distasteful and disturbing. It should not be encouraged for, in denigrating Mr. Linton in this way, he has raised doubts about the competence of the Judiciary of the Eastern Caribbean Supreme Court in which Mr. Linton's Appeal was upheld. Happily, the tendency to reckless denigration is not widespread. In fact, I cannot find two Dominicans who indulge in that level of smear as habitually and as enthusiastically. That is the bright side. May that propensity, therefore, never to take root in our evolving Commonwealth. It is not indigenous. It is not even Caribbean. It is noxious and exotic.