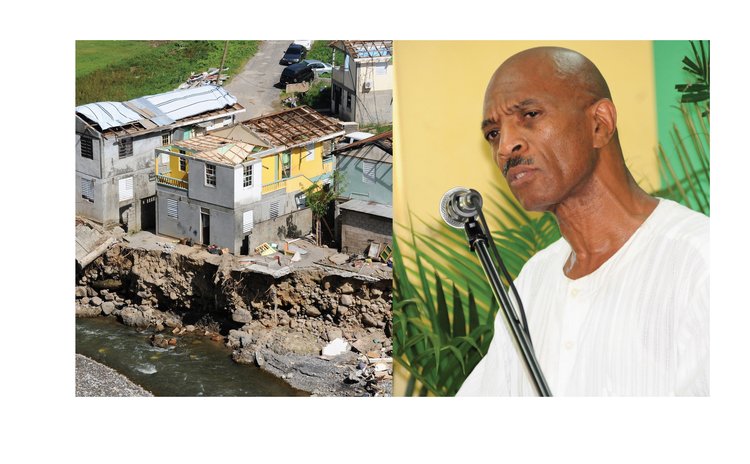

Forget that first climate change resilient nation thing

It was possibly the most commendable commitment made in the wake of the killer storms of 2017, an admirable ambition that received praise of the highest order.

But, with the start of another hurricane season and no visible signs of the first step towards realising this conceit, is the pledge by Prime Minister Roosevelt Skerrit to make Dominica the world's first climate resilience country an achievable one? Is it even original?

It's the question many are asking, and it's one addressed by one of Dominica's leading development experts and a keen observer of all things climate.

"Being the first is a laudable aspiration, but there . . . are a lot of other countries . . . that are pushing that," Crispin Gregoire, a diplomat and former ambassador to the United Nations, told The Sun.

"This notion of being the first is just a catch phrase. I have taken a position to support the climate resilience efforts, but the 'being the first' thing, I am not sure about that."

Gregoire says countries with greater resources than Dominica can ever dream of having, are already working towards climate resilience.

Among them is Japan, which in November 2015 published its national plan for adaptation to the impacts of climate change, which establishes the basic principles for promoting systematic, integrated and coordinated efforts to address these impacts on the East Asian island nation.

The aim of the plan is to minimise or avoid damage from the impacts of climate change, and "create a secure, safe, and sustainable society that can quickly recover from those impacts", according to the cabinet decision of 27 November, 2015.

"To avoid rework and to promote timely and appropriate adaptation, the government will continue to observe and monitor climate change and its impacts, ascertain the latest scientific findings, implement regular assessments of climate change and its impacts, consider and implement adaptation measures in each sector based on the results of the impact assessments, assess progress, and revise the plans as required.

"By repeatedly following this cycle, the government will work in a unified way to systematically promote adaptation to the impacts of climate change," the Japanese cabinet document says.

While António Guterres, the United Nations secretary general, lauded the Skerrit vision during a visit here last October to observe first-hand the devastation caused by Hurricane Maria, and while the international community has promised hundreds of millions of dollars in assistance, there are no visible signs that government is moving is this direction and, unlike Japan, there is no published plan.

"The task is so daunting it is going to take a lot of time. It could be 20 years before we begin to make progress," Gregoire surmises, while he goes on to question the object of the prime minister's attention.

"His focus is hurricanes, but our biggest challenge is sea level rise and he is not focusing on that. Because sea levels are beginning to rise, we have communities that are under threat. Villages like Loubiere and Coulibistrie are under serious threat," the diplomat warns even as he applauds Skerrit's stated intention to construct buildings that withstand extremely powerful storms.

However, it is the announcement of plans to make Dominica the first climate resilient country in the world that Gregoire questions.

With few resources, almost total dependence on the international community, and no obvious plan, he suggests that it is nothing more than a glorified romantic notion.