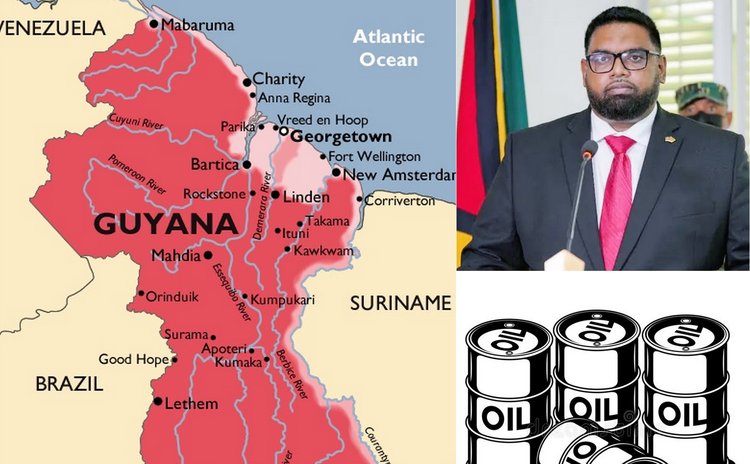

Guyana's New Oil Wealth

Lessons for Dominica from Guyana's oil-wealth saga

ExxonMobil (Exxon) is developing Guyana's offshore oil industry at a lightning pace with the government's blessing. Exxon and co-venturers Hess Corp and CNOOC Ltd enjoyed quick success at the Stabroek Block thanks to a favourable deal, ample supplies of high-quality crude, ready markets, and low breakeven prices. But how is the oil wealth reaching the man in the street, and what lessons can Dominica glean?

Exxon has made 30-plus world-class finds in the Stabroek Block since the first oil strike in 2015, pushing estimated reserves to 11 billion barrels, with 35 exploration wells on the cards in 2023, anticipating further high-quality oil discoveries. As a result, oil exports surged 164% from an average of just over 100,000 barrels per day (bpd) in 2021 to over 225,000 bpd last year. By the end of February, the Liza Destiny and the Liza Unity floating production storage and offloading (FPSO) vessels were pumping at least 380,000 bpd. A third FPSO-Prosperity-arrived on April 11; its startup by yearend would add 220,000 bpd.

Guyana's macro-benefits are impressive. Oil revenues reached US$1.09 Billion last year, up from US$607.6 million in 2021. The World Bank (WB) ranks the economy as one of the world's fastest-growing; growth rates averaged 31.7 per cent over the last two years, with double-digit rates predicted for 2023-2024. "Real GDP is estimated to have increased by 57.8 % in 2022, owing primarily to an expansion of oil production," the Bank said. Buoyed by this, the 2023 Budget featured a 140% increase in development spending and plans to double the capital investment. In addition, a Low Carbon Development Strategy is in place to stimulate other sectors, uplift entrepreneurs and small businesses, and provide training to fill skills gaps.

Managing New Oil Money

To facilitate this, the government has introduced a raft of policies, changed legislation, activated mechanisms for land-value capture, and established a Natural Resources Fund (NRF) to manage oil revenues. In addition, oil industry job creation is a priority, driven by a novel Local Content Secretariat. However, the showpiece project is a US$1.7 Billion gas-to-energy joint venture with Exxon-a natural-gas-fired power plant and natural gas liquids plant-projected to save Guyana US$500 Million, cut consumers' electricity costs dramatically, and catalyze trade and commerce.

When Exxon struck oil, Guyana lacked the skills to fulfil industry requirements in many technical areas. As a result, Exxon and other industry players have been providing specialized training and education to Guyanese. For example, Guyanese graduate engineers got hands-on training on the Prosperity FPSO in the Netherlands, Singapore and Monaco and will support the operations of the vessel. Several new educational institutions are offering industry-specific training.

Significantly, oil funds cushioned the economy during the COVID-19 pandemic, severe flooding in 2021 and the fallout from the Russian invasion of Ukraine, allowing the government to share cash-relief packages, according to the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

The oil industry has generated multiple spin-off business ventures, trading opportunities and jobs for Guyanese, especially in agriculture, food services, mining, construction, logistics, recruitment, and service sectors. In particular, there has been an explosion in demand for food, transportation and other services for the FPSOs offshore. Overall, many ordinary Guyanese are acquiring skills and jobs with oil and gas companies and their suppliers.

Poor people are not feeling it yet

However, the trickle-down of wealth to the poor might be slower than many expected.

Up to last November, the WB reported that around 48% of Guyanese still live in poverty, among the Region's highest rates. However, in an ongoing "How the Cost of Living is Affecting People" series, Stabroek News found common ground among some ordinary Guyanese.

Curt Joseph stated, "I can't afford to buy certain things in the market because everything is expensive…I can't save because I'm spending more these days." Nalisia Rodrigues concurred, stating, "The cost of living gone up high, especially when you have children… when I finish buying things for the children, I hardly could buy groceries."

But in 2022, the IMF reported that, despite the large human development need, public investment spending "will increase in the medium term, to close infrastructure gaps and to support development needs, helping growth in the non-oil economy". According to the IMF, "Guyana's medium, with increasing oil production having the potential to transform Guyana's economy profoundly."

As anti-oil activists continue to rage against the generous oil deal and what they see as secret dealings and cronyism between the government and oil-sector bigwigs, Exxon has gone full steam ahead under a "power to the people" banner. The company launched the Greater Guyana Initiative in 2021, a 10-year commitment of more than US$100 Million to significantly expand capacity-building efforts and promote sustainable economic development in Guyana.

Analysts attribute much of Guyana's poverty-reduction challenges to race-torn politics fueling ethnic insecurities with accusations of endemic corruption and mismanagement of national funds rife. The mainly Afro-Guyanese opposition political parties say oil money and contracts go primarily to Indo-Guyanese government supporters and their enclaves, while ruling party loyalists oversee the NRF. "What they're seeking to do is use oil for political patronage," said Opposition leader Aubrey Norton. The government strongly refutes these claims.

Lessons for Dominica

There are valuable takeaways from Guyana's oil saga. First, national unity is critical; political division comes with a hefty cost and stymies the equitable distribution of benefits, especially to the poor. Also, maximizing benefits for locals in foreign investment deals is essential; and environmentally-conscious development of natural resources-like Dominica's geothermal energy-requires maximum risk management and insurance. In addition, revenue from such assets must go towards fixing issues like high public debt, inefficient public infrastructure, non-performing State-owned enterprises, and capping the rising cost of living. Finally, robust accountability and transparency in fiscal management are indispensable; otherwise, sudden new wealth cannot help the poor.

Most of all, as a carbon sink nation like Guyana, Dominica should explore getting First World nations to pay the island to keep its environmental treasures intact and seek full compensation for what it would lose by not damaging the environment in a quest to raise its most vulnerable residents out of poverty.