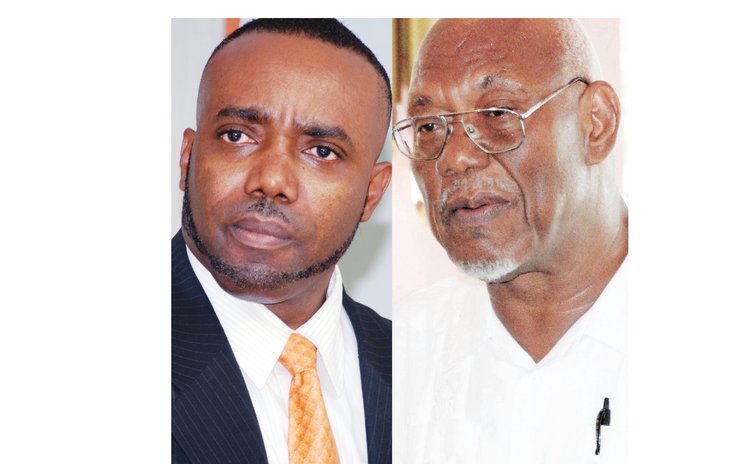

Johnson Commission hard on Minister Blackmore in final report

It was its final act, and the Integrity Commission led by former cabinet secretary Julian Johnson did go quietly.

In its last report before the Commission was disbanded and replaced with a smaller, more controversial body, the Integrity in Public Office (IPO) Commission ripped the Minister of Justice and National Security, Rayburn Blackmore for failing to table the previous report in parliament 13 months after it was due.

In a letter dated 10 December 2015 that accompanied the seventh annual report for the year ending 31 August 2015, the Commission all but accused Blackmore of violating the very law he is sworn to protect by not tabling the sixth report. The first letter was sent to Ian Douglas in his capacity as Minister for Legal Affairs on 1 September 2014, and sent to Blackmore on 30 January, 2015.

"In this report, the Commission expresses its concern that after thirteen (13) months the Sixth Annual Report to Parliament has not yet been tabled in the House of Assembly and again urges the Minister to comply with the section 48(1) mandatory directive, without further delay," Johnson wrote.

"It is a general principle of governance in constitutional democracies that the exercise of public power in all its forms and by all state authorities must be accounted for to the public.

"The failure to table the Sixth Annual Report invades the province of Parliament and prevents it from exercising the scrutiny and review function immanent in section 48(1) of the Act, on behalf of the people of the Commonwealth of Dominica. The Minister may wish to inform the Commission of the compelling reasons for his inability to comply with the statutory duty in this instance."

It was a damning indictment on the administration of Prime Minister Roosevelt Skerrit, who earlier this year, amended the IPO Act, reducing the number of commissioners from seven to three, and dumping Johnson and the remaining members of his team.

The Johnson commission had earlier recommended amendments to the Act, to include provisions that would allow the commission to submit its report directly to the speaker of parliament for presentation to the house of assembly, should the minister fail to lay it in parliament. The Commission had also recommended cutting the number of members to five.

Skerrit ignored both recommendations when his administration amended the Act this year.

The Johnson commission was even more damning in its criticism of the minister in the actual report, warning that his failure to table the previous "strikes at the very fabric of our parliamentary system of governance" and was a violation of the constitution.

"Those who exercise public power must act in accordance with the Constitution and any other relevant law," the report states, stressing that mandatory language of the law were clear regarding the strict deadlines for compliance.

"The Integrity Commission again urges the Minister: (i) to discharge the mandatory statutory duty under section 48 of the Act, and (ii) to make public the reasons for not doing so during the past thirteen months."

The last report also revealed a tacit disregard of the commission by the president, Charles Savarin, whose refusal to report his assets for the period up to September 2013 when he served as a minister until his elevation to the presidency resulted in a legal battle between the Commission and the Attorney General.

It makes reference to a letter written to Savarin in 2014, advising the appointment of a three-member panel of commissioners to probe and verify the contents of certain financial declarations that had been filed with it. It does not list the declarations with which it had concerns, however, it says Savarin disregarding its advice and appointed three members of his own choosing.

"The Commission is of the view that section 23(3) of the Integrity in Public Office Act does not provide for the President to appoint a Tribunal in his own deliberate judgment," the report states. "The words of section 23(3) are clear, unqualified and unambiguous. The President must appoint a Tribunal consisting of three members of the Commission on the advice of the Commission."

It adds that the tribunal "purported to be appointed" by Savarin was illegal and that the president's panel did not take the oath of office, nor did they begin the probe.

"The Commission wrote to the President detailing the matter and requesting that he should reconsider and appoint the Tribunal as advised by the Commission in keeping with the provisions of the Act. The matter remains unresolved," it states.