Much ado about nothing

Dominican development experts say CPO21, the recent Paris agreement on Climate Change, is not much to shout about as far as Dominica is concerned

Caribbean countries celebrated.

"Our delegations witnessed a sincere interest to craft a fair, balanced and ambitious agreement that sought to address the needs of the most climate-vulnerable countries," said Dr James Fletcher, the chairman of the Caribbean Community (CARICOM) task force on climate change and St Lucia's sustainable development minister, who was pleased that "for the first time in a long time" small island developing states (SIDS) felt their concerns were being heard at a meeting on climate change.

The Caribbean boasted.

"Never before has the Caribbean been as united and as single-minded in an international conference of that importance," stated Dr Didicus Jules, the director general of the Organization of Eastern Caribbean States.

The Caribbean held its breath.

"This new agreement offers hope," concluded the Caribbean Tourism Organization.

Yet, amid it all, development experts and environmentalists here believe the recent Paris deal on climate change is hardly much to throw a party over.

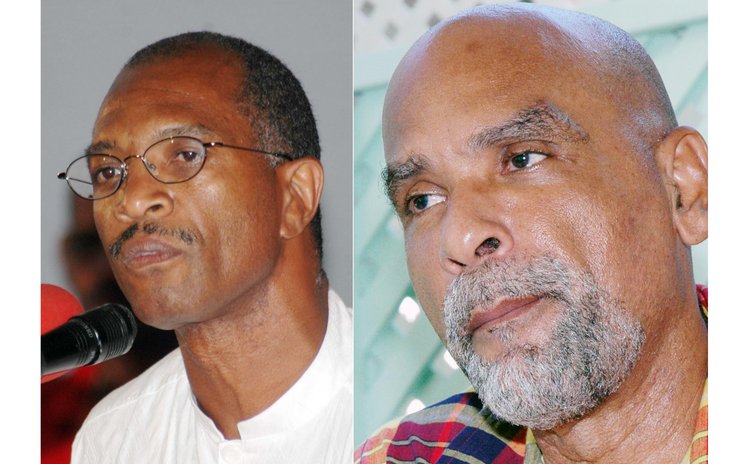

Yes, the fact that the 195 countries reached a covenant suggested there was progress, agreed Crispin Gregoire and Arthie Martin. But there is little else to celebrate, they concluded.

"I don't entirely discount it as useless, it is not useless. But we have to be really very careful not to pin our hopes on events like the COP21," Martin said of the 21st Conference of the Parties, as the climate change meeting is called.

"It gives some hope because where [the 2009 United Nations Climate Change Conference in] Copenhagen failed we were able to get an agreement. But it's nothing to shout about," added Gregoire in an interview from New York. "We have an agreement, that's progress on one hand, but countries really have to live up to their responsibilities otherwise the agreement is meaningless."

The final document from the talks reflected consensus among nations for a two degree rise in temperature limit above pre-industrial levels, while working towards the limit of 1.5 which was a SIDS demand. The agreement also made reference to loss and damage but was noncommittal on this and the issue of liability.

"I'm disappointed it's not a legally binding agreement and it doesn't commit any of the countries that created the problem in the first place to fix the problem," Gregoire complained.

Martin went even further, insisting that the responsibility should have been placed on the shoulders of the big international companies that pollute and damage the environment.

"I don't think it really means a whole lot for us [in Dominica]. What they needed was an airtight, legally binding, financially binding agreement from the corporations. The governments basically do the bidding of the corporations and the governments protect the corporations. I think the wrong people were at the table, in a sense. It's not an agreement that will make any measurable difference beyond climate change," Martin told The Sun.

Having experienced one of the worst storms in its recent history when Tropical Storm Erika hit in August, Dominica has come face to face with the impact of climate change.

Gregoire said it would have been good if the issue of damage were more emphatic and if there had been a firmer commitment to financing, particularly for clean energy projects.

"For us in Dominica we need money for geothermal, we don't have that money. We need help to reengineer our agriculture to make it climate resilient . . . Here we are, we have just been hit by a storm, we have been set back 15 years and we didn't get money to rebuild.

"So we are being ravaged by the impact of climate change, our fishermen . . . the fish is getting lower, our coral reefs are bleaching …so it's bad. What we are facing is very, very grave. And I'm not satisfied, that the small states, we didn't get much," the development expert said. He applauded the decision to keep temperature rise to two degrees and to strive for 1.5 degrees. However, he said this was not enough.

"Sea levels are rising… Newtown, Massacre, Mahaut, Coulibistrie, all these places are under threat because they are so close to the sea . . . Because it's not legally binding, will the countries be committed to do what they should be doing? I'm not sure.

"For us the issues revolve around warming, mitigation and financing and the threats we face from many areas. Sea level rise, extreme weather conditions, long periods of drought, the future of agriculture and how are we resilient in terms of our food production. Fish production is being affecting by warming oceans and acidification of the coral reefs. The real question is, who is going to help us?"

Not the big countries and certainly not the major corporations, argued Martin who encouraged people to get involved at the grass roots level.

"In the final analysis it's only work on the ground level that is going to cut it because if people at that level don't insist . . . no international agreement is going to filter down before 20, 30 years."

The Paris Agreement will succeed the Kyoto Protocol, the last international treaty on climate change. It is due to take effect in 2020, and calls for developed countries to bear the cost of financing the transition towards a green economy.