We Cannot Youth-Proof Society

I open with a standard disclaimer for those who won't read this article before analyzing its content. There are some among us who care enough to make the time to listen, to share, to learn and constructively engage, and we should allow them to.

"Treat the youths right, instead of putting up a fight; treat the youths right, or you'll be playin' with dynamite" – Jimmy Cliff.

I begin this reflection by stating that yesterday's teachings inform today, and the experiences of today will shape tomorrow's message. It is an established fact that energy drives the message, and the ones with most energy and purpose to drive any message, in any era, are younger people or youths, teens, millennials. Call them by any name, but younger people everywhere are the same. Changing times and different era do very little to change youthful passion.

Youthfulness is a blessing; and experience is knowing the value of the blessing. When I was younger, those with experience – the great majority of them – did not appear to appreciate my views, so I will do all I can to help shield the youth from this attitude. We need creative and youthful energies to drive nation-building, and the easiest way to achieve this is for the system to allow the youth space to create. There is indeed a great synergy between youthfulness and experience, and when we find the right balance, we will become a much better people.

This article is composed from a Dominican perspective, but reflections contained therein are not mutually exclusive to Dominica, nor the Caribbean region. I say so because of the unbroken connection which exists among youths – the world over – and this vibrant community will occasionally wake up to check the authority of those who hold power within the system. In fact, youth have been at the center of riots, protests, and other such movements of change. Dating back to the mid-1960s (the period under review in this article), youth around the world became attuned to social issues. Events like war, poverty, hunger or starvation, and other socio-economic matters became part of the youth activism agenda, and they rallied against this. So, this has been happening, especially as the political culture of our nations continued to change in the 70s, 80s and 90s.

Youth activism is at an all-time high. On September 20, 2019, there was a coordinated, global strike (at school), which included 150 nations. The action was waged against global leaders, and corporations because of their passive attitude towards climate change. The initiative was led by "16-year-old Swedish climate activist Greta Thunberg, the original school striker who last year [in 2018], began demanding more action from her government on climate change with weekly protests" (Umair Irfan, September 20, 2019). Thunberg became increasingly influential, and her influence has served as a catalyst to other young people, including the Dominican youth.

The long and short of it is that, there has been shifts in the Dominican political landscape, and though we may not readily witness that change in real time, there are occasional manifestations which make us aware that things have shifted. From the very pinnacle of the state's authority to the citizen who is most unattached to matters of state, there have been eyebrow-raising utterances which do not need repeating here. If commonsense does not prevail in the leadership of present-day Dominica, something will eventually give. The next generation may have a thing or two to say, and we had better prepare to listen and act, or feel.

Today's realities are today's realities, and it cannot be all good to try and teach yesterday's values today, without first understanding the issues of today. It is also counterintuitive, in my view, to set standards on others based on one's lived experiences and circumstances. Yesterday's children are not today's children and today's children will not be tomorrow's children- our world is evolving. People grow up in different eras, so things will be done differently, from one era to the next. I am of the firm opinion, based on my work in the Dominican communities, that today's children are misunderstood and /or are taken for granted. This sets up a scenario which the system can ill afford, because the disparity between the youth and society's realities are much too great. Youth unemployment in Dominica was – the last I checked – at about 45%, and this may even be higher now, thanks to COVID – 19. The youths are therefore hungry, and when people are hungry, they can easily get angry.

As was mentioned earlier, this article concentrates on youth action, and to place a present debate about Dominican youth behavior in context, I revisit past Dominican youth behaviors. The Dominican youth come from a deep root of struggle and rebellion, and the present youth who believe that s/he is not part of that struggle, is indeed part of the experience. The struggle began with the system of authority, and the lawful oppression (force subjugation), exploitation and mischaracterization which it promulgated. As time passes by, the system merely adapts to the changes and repackages its control measures, while the youth keep fighting to belong in successive generations of society.

To narrow-down my argument, I decided to look at the Dominican youth resistance of the late 60s and 70s, and track the path to 2020 - a period which stretches half a century and more. This exercise is meant to connect the decades in order to make a contemporary point about Dominican youth. So, it would be unfair to equate or even compare and contrast those periods (late 60s/70s and 2020), because each era stands on its own terms and should be placed within its own context – even if there is obvious connectivity.

The world was gripped in racial struggle during the 1960s. America, which had emerged as a world super power following WWII, became the lens through which the world would see humanity. The BLACK v WHITE struggle wages on, and racism and racial attitudes were experienced in real time. The youth jumped into action. From Rosa Parks and her refusal to give up her seat to a white passenger on a Montgomery, Alabama bus in 1955, to the ascendancy and message of hope and unity and the consequent assassination of President John F. Kennedy (JFK) in 1963, to the Civil Rights Legislation which was signed by President Lyndon Johnson in 1964, and the temporary muting of the voice of Dr. Martin Luther King (MLK) in 1968, and all the other related atrocities of that era; a platform for rebellion had been laid. Black Power became a chant, and resistance to the authority spread as a pandemic which impacted power structures the world over.

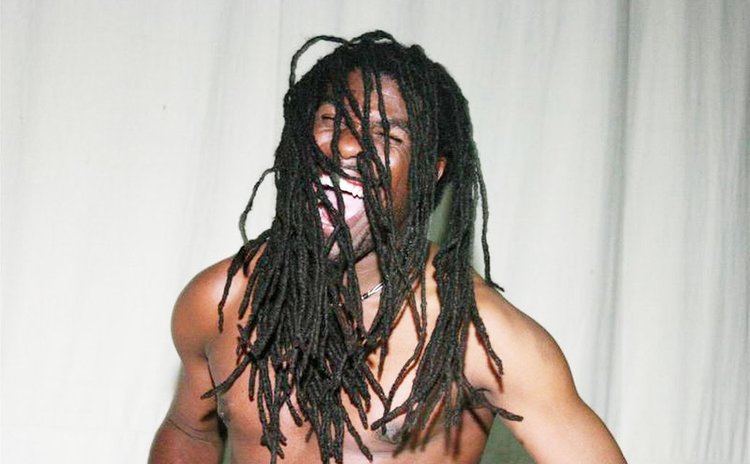

This chant was led by the youth, and that very attitude was present in Dominica. It was the prevailing conditions of oppression, and the will to prosper which pushed the liberal-thinking youths to embark upon a journey of self-rediscovery. This mission which was powered by Rastafarianism – a religious movement popularized by Bob Marley during that same era (mid70s) – took the youths to the hills in their fight against the system. Essentially, the fight against the system was a move away from the system. Scores of Dominican youths retreated to the hills and decided to set up their own civilization. There were two categories of rebellious youth: Nonm tè and Dreads. As a former nonm té explained to me: there are distinct differences between nonm té and dreads, but the system and the law characterized both groups as dreads.

The nonm tè (man of the soil, man of the land, or roots man) were those men (nonm in Creole) – and women as well – who chose to rely upon their own means for survival; they survived from the land (té in Creole). Nonm té abandoned society and set up their own; a system of livity where they cultivated the land and produce their own food. The nonm té ate what they grew and grew what they ate (and smoked), so that mantra eat what you grow and grow what you eat was borrowed from the era of Dominica's nonm té. The nonm té also stayed away from Babylon (the system) and the law, and they sought to lure other youths out of the system and into the hills.

Dreads, on the other hand, were angry at the system, they looted, plundered and even killed people from the system (mainly farmers) in their agitation against the system or Babylon. Dreads chanted down what they viewed as an evil and oppressive system of authority, and they had several physical interactions with the law. They accosted ordinary citizens and even abducted young Dominican women, and kept them for a prolonged period up in the hills. Unlike the norm té, dreads were relentlessly rebellious and unwittingly provocative.

The system and the law had to fight back, and since both sets of youth were up in the hills (a place where both groups referred to as Zion which is the establishment of a homeland within a wider space), and they carried similar physical features, the system sought to rid society of all of them on account of the behavior of just a few – the dreads. The hunt was on for the dreads and it was brutal, forceful and unforgiving.

The Prohibition and Unlawful Societies and Association Act aka 'The Dread Act' of 1974 was drafted, operationalized and used to fuel the search for the rebels. I should state, for the record, that the Dominica House of Assembly bill which was proposed by Prime Minister Patrick John, was passed unopposed and with strong support from members of the opposition – The Dominica

Freedom Party (DFP). Prime Minister John was leader of the Dominica Labour Party (DLP), a then staunch political rival of the DFP. In short, the act was widely accepted, and unabated legal immunity was granted to law enforcement officers; they were immune from prosecution for assaulting or murdering Dreads, Rastafarians, Nonm té – anyone with dreadlocks.

Rastas were denoted, by law, with having locked hair (dreadlocks), and many be-locked youths were hunted down and killed during this seditious era, until a 1975 amnesty which was offered by the Dominican government, helped ease tension between dreads and the authorities. As I said before, law officers were also attacked by the dreads. I should also say, for the records, that though the official inquiry which was set up by the government to look into the activities of the Dreads or Rasta civilization proved that the overwhelming majority of the youths were peaceful activists, the government flatly rejected its findings.

That was then, so let us fast-forward to the present, 2020. Let me fill the gap with context that might help to guide the analysis, and assist in making the connection. Patrick John was overthrown as Prime Minister in a popular national uprising in May 1979 (6 months following Dominica's independence). The Dominican government fell and an interim regime, the committee for National Salvation led by Oliver J. Seraphin, was put in place to pave the way for general elections. The DFP swept the polls in the 1980 general elections (winning 17 of the 21 parliamentary seats – the newly formed Dominica Democratic Labour Party won two seats and two DFP-leaning independent candidates won the other two seats; the Dominica Liberation Movement (DLM) also contested elections for the first time. The DFP ruled for 15 years (1980 – 1995). The United Workers Party (UWP) seized power from the DFP in 1995 and DFP and DLP created a coalition which held the majority position in the Dominican government in 2000. The arrangement is still in place after 20 years. The previously listed statement should allow for a more informed placement of the current behaviors, and attacks against, the Dominican youth.

I am not suggesting that the prevailing matters of the 60s and 70s are similar to those today. We have evolved and circumstances are certainly different, but the public rebuke of all youths on account of the action of one or some in the present time, warns us about past mistakes when we painted the Dominican youth with a broad brush. The system of authority is properly armed with its supporters, defenders, cronies, fanatics, friends, and others who can be as effective – or even more so – as any act or parliament. It is evident that law enforcement mainly protects the authorities instead of serving all the people, and this raises the issue of vigilante justice – a matter which I will discuss sometime in the future. Let me put it bluntly: the idea of the peoples' rights to speak freely on issues which affect them, seems to be under siege on the island of Dominica. I should also bluntly state that right come with duties and duties demand responsibility. Each citizen has the duty to respect each other's rights, so 'free' speech and other such manifestations can encroach on rights. Behaviors and actions should be checked on all fronts.

The matter of rights, duties, and responsibility can be used to characterize behaviors. One may take an action which would differ from the actions of others, so all, therefore, should not be grouped in that action. There is, however, the matter of complicity. One can be culpable of a collective action by refusing to intervene, thus allowing inhumane and criminal actions to persist. This was clearly seen in the police-killing of George Floyd in Minnesota, USA, on May 25, 2020, when three police officers simply stood by and witnessed another officer squeezed the life out of an unarmed man who was already in handcuffs and posed zero threats to the officers. Ironically, this matter goes to the roots of inequality, injustice and the abuse of law and authority; a common cry in Dominica at the very moment. It would seem as if the penumbra of that bright light which is now focused on America is showing-off the inadequacies in other parts – certainly in Dominica.

There is need for collective action in dealing with systematic inadequacies or unfairness. Generally, it is the youth who have taken action in every society, so, if the Dominican youth, in 2020, feel and believe that they must take a stance against the erosion of their rights and privileges, they should do so. Some will act civilly and some won't. Civility is determined by the civil authority and whatever action the authority deems as not being civil, is uncivilized. We saw this in the swift action of the authorities, when the prohibited society set up by dreads was dismantled during the mid-70s. It has been proven that aggressive tactics may not always be the best option, especially when dealing with people whose causes for aggression may not have been properly addressed, and who also have little to lose. While some will be aggressive, we should always seek to understand the cause of their aggressive behaviors.

Mahatma Gandhi and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. taught us that there are 'civil' means and 'peaceful' tools which could be used in settling aggression, especially state-sanctioned, sponsored, approved and perpetuated aggression. But the state does not play by the rules of peaceful engagement, and it is a reaction to the state antics that I am addressing here. It would appear that peaceful means are mocked, especially by more authoritative state authority – the likes of which exists and is very well entrenched in modern-day Dominica. Probably this observation can explain the dispersive outburst of a Dominican youths while on a live and public social media exchange with the Hon. Prime Minister of Dominica. I will not mention the many instances when he, the same Prime Minister, has dished out similar or worse insults from his Prime Minister's pulpit, but wrong does not cure wrong so I will resist the urge to bring up the matter of poetic justice.

It is painfully clear that the political culture of our nation has changed. Bad is now good, and bad deeds are praised by people who were once seen as 'good' people. In fact, bad is bad based on who does bad, and good is bad in the same way. The history of political partisanship in Dominica has set us up for the dramatic end of an era. We are on the crust of a new political dispensation, and the youth will again rise to take action. The youth will raise their voices, not necessarily for partisan causes, but because they want to progress. We need to listen. The youth need an active role; they will not be used as political tools. The youth are ready to lead, and they won't mind being led by people with sensibilities towards the youth. There must be sensible compromises, dialogue and realistic expectations. We cannot afford to drown-out the voices of young people, nor should we seek to control or manage their perspectives of progress. If Dominica is to move from the present state, youth must have a major role, as leaders, of that movement.

We may not be able to erase the effects of the past, but we can learn from it so as not to repeat the same old mistakes. Introspection is needed. We should be pragmatic with our present actions, and the future should be one where all our people will enjoy the blessings of nature, equally, and to the fullest extent of our capabilities. For this to be the case, we need to work on the foundation. If the youth "disrespect" the system's rulers, the rulers should engage the youth – not disrespect them in return. But the youth should not be unwittingly disrespectful, because respect goes both ways. If the rulers engage, meaningfully, the youth will respect the rulers. When the rulers disrespect society, the youth will disrespect the rulers, and they will speak out and may even lash-out. This is an established trait in societies the world over, and as was explained, Dominica does not have immunity to this.

Youthful energies have always driven protest efforts. It has also been proven that, given the right incentives, people will commit the most bazaar act(s) – even forsaking their own families in their own selfish pursuits. Hence, I am not alarmed by the behaviors of some who seek to discard dissent as insolence. Moun sewyé, a group of rebellious younger Dominicans, are now leading a protest against the Dominican authority. They should not be aligned to negativism nor maligned as outliers. We should embrace the opportunity to dialogue with and understand them. After all, the present rebellious elements within the Dominican society now preach what the nonm té preached over half a century ago: that we should give them an equal chance to survive; that we should eat what we grow and grow what we eat; that we should get back to the soil and practice conscious and clean levity; that this Babylon system which seeks to oppress agitators should come of age with the rhythm of the time; that all injustice should cease; that corruption in high place should be relinquished; and that political power is a false sense of comfort or security.

The chants of moun sewyé is a microcosm of the anguish that today's youth feel. Some hear it and some pretend not to hear it, but we all know it, or have experience it, or aware of it and we should look into it. The young people of our island need a fair break, and it must be addressed in a way that wipes away the malaise of political tribalism which has all but eroded the Dominican way of life. Frankly, I see an approaching crisis, but it is one which can be averted if only the stiff-necked controllers of the present system would pause a bit, put away their hardened selfishness and listen to the sentiments of the people. Those who now govern Dominica should not pretend not to be hearing the cries, because those cries are too loud.

I now refer to statements which were offered by Dr. Hazel Shillingford-Ricketts following the arrest of members of moun sewyé in the wake of their strong agitation against the Dominican government. Dr. Shillingford writes: "yesterday [May 28, 2020] I commented on the inhumane act that led to the death of a black man in the USA. This act was perpetuated by a police officer resulted in widespread unrest. Worse is that it happened during the covid-19 pandemic when social distancing is paramount". She added: "then I reflected on a current situation in Dominica. Young men expressing their views in a video on social media. This resulted in the arrest of a number of them. The police have reacted in the interest of law and order. Have we as a society listened to these young men? They have taken ownership of their frustration with the governance of Dominica. They have expressed the need for action to what end, to the detriment of who, when and how? What was most telling in Dr. Shillingford-Ricketts' statement, however, was when she remarked that "we just remembered May 29, 1979. As a 20 year old I lived through this uprising in Dominica. There were many stage leaders including our current President as a trade union leader, religious persons, business men, and others, but the destructive forces were from the fearless, untamed, and rudderless energies of the young people. Dr. Shillingford-Ricketts said, "we don't want to unleash this type of energy from our young people again", and I totally agree.

The good doctor certainly sets up the finale of my article. It is my view that the last half century of Dominican politics was presided over by players, many of whom, who either did not, and probably cannot appreciate the true value of the Dominican youth. There is a general mentality which clouds political participation, and it is that, if you want to get involved, you should pick the winning side because if you lose you will suck salt (this was in fact said to me by a friend and noted political scientist). Because of this, many young people (and other people) chose to remain out of the political grid, and the system rolls along being youth-proof. But this has been shifting, and the debris from past resistance will eventually wash up on the shores of present-day Dominica.

It is also my opinion that, just as the youth were a major part of the struggle to amend the political discuss and upset the status quo in the 70s, so too will they participate in amending the present political discuss and upsetting the status quo. Those who are not ready to embrace reality will be consumed by it, and those who believe that the peoples' power is eternally vested in and/or willed to them, will learn too late that they were wrong.

Young people have been the catalyst of social change and mobility, and if any country on earth is in need of such mobility, Dominica is that country. We definitely need a new kind of politics on the island of Dominica and in the Caribbean region, and younger people are prepared to flavour that new politics. That much I know because, through my work with younger people in the classroom and in the wider society, it is evident that younger citizens believe that the system genuinely attempts to youth-proof society by drowning-out the most pressing concerns of millennials.

May the spirits of all the youth who have died in the struggle be pleased with my intervention.